Navigating Complex Currents: A Multi-Theoretical Approach to ADHD Case Conceptualization at BHCS

Chris Berman | Apr 30, 2024 | 26 min read

The following case conceptualization will focus on a client seen at Behavioral Heath Consulting Solutions (BHCS). Throughout the conceptualization, the client will be referred to as Michael, a pseudonym to protect the client’s identity. The client’s identifying information, presenting issues, relevant history, and diagnosis will be discussed in detail, followed by a multi-theoretical conceptualization and treatment plan. The client will be conceptualized through the lenses of cognitive behavioral theory (CBT), relational cultural theory (RCT), and psychosocial development theory (PDT).

Client Description

Identifying Information

Michael is a 28-year-old Caucasian male who identifies as cisgender and heterosexual. The client lives in Billings with his wife, to whom he has been married for four years. He is a salesperson at an automotive equipment and supply company and is considering attending college to become a computer engineer. Michael has attended eight telehealth counseling sessions with the counselor. He was referred to BHCS through a counseling friend of his who thought that he should be screened for neurodiversity. The client underwent a thorough diagnostic assessment process, and it was determined that he has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which will be discussed in detail below.

Mental Status Exam

Michael consistently arrives for counseling sessions on time and is enthusiastic and motivated to improve his mental health. His motivation is evident in his excitement to learn and explore his recent ADHD diagnosis and the medication that his psychiatrist prescribed. The client appears to have good hygiene practices, as affirmed by neatly combed hair and clean-looking clothing. He engages with the counselor by making regular eye contact, although he will divert his gaze when describing challenging or emotional situations.

The client presents as oriented to person, place, time, and situation. His affect is congruent with symptoms of ADHD, including fast-paced speech, excitability, fidgetiness, and interrupting the counselor often. The client’s thought process frequently takes him off-topic from the counselor’s questioning, as evidenced by tangential descriptions and stories. The client denies having hallucinations, delusions, and suicidal or homicidal ideations. Further, the client denies any mental disorder history in his family. He displays appropriate judgment and above-average intelligence and is self-aware and reflective of his internal thought process.

Presenting Issues

The client sought counseling due to concerns about anger management, emotional reactivity, and his suspicion that he might have ADHD. Michael stated that his anger and emotional outbursts have caused significant trouble in his marriage. He described fights with his wife as being very volatile.

The client expressed insecurity about attending college due to his inability to sit still through high school classes, stay focused, and pay attention. He compared himself harshly to his two sisters and father, who are successful in their careers and have master’s degrees. He said that he feels that his undiagnosed ADHD presented many challenges in his life, including his strained relationship with his father and marriage; for this, he has grown insecure about his abilities and has judged himself harshly.

Relevant History

Michael grew up in a middle-class home in Seattle, Washington. He shared that his father was an English teacher at his high school, and his mother stayed home to raise Michael and his two older sisters. The client revealed that while both of his parents loved and provided for him, they were emotionally distant and fought with each other often. Further, the client stated that his father had a very traditional view of masculinity, one that emphasized strength and toughness and discouraged any signs of weakness or emotionality.

While Michael was a skilled athlete in high school, he expressed a greater interest in art and music. He said that these mediums gave him a way of understanding the turmoil at home and a way to express his emotions, particularly sadness and anger. After high school, the client moved to Missoula, where he honed his landscape painting skills and played guitar in a popular local band. He said that he met his wife in Bozeman, and in 2022, they moved to Billings to be with her family.

DSM5-TR Diagnosis and Justification

Criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual's fifth edition (DSM-5-TR) were utilized in creating a diagnosis for Michael (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2022). Additionally, the client was administered a thorough assessment through BHCS that screened for mood disorders, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, mania, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorder. In considering potential diagnoses, the counselor must first rule out medical conditions and substance use as contributing causes for symptoms (Morrison, 2014). The client denies having any significant medical conditions. The client stated having used substances, primarily cocaine, in the past, but he has abstained from it for two years, and the counselor does not believe this is a contributing factor in his presenting issues at this time.

The client meets the criteria for both inattentive and hyperactivity/impulsivity ADHD in the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022). Additionally, his scores on the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale indicate symptoms consistent with ADHD as well (Kessler et al., 2005). The client meets six criteria in criterion A1 for ADHD in the DSM-5-TR, most notably difficulty with sustained attention and avoidance of tasks that require sustained mental effort (APA, 2022). Further, the client meets seven criteria in criterion A2 for ADHD in the DSM-5-TR, most notably his tendency to talk excessively, interrupt others, and act as if “driven by a motor.” (APA, 2022, p. 69). Additionally, the client meets ADHD criteria B-E of the DSM-5-TR: He reports that his father recognized ADHD symptoms in him before the age of 12; his symptoms occur in several settings, the symptoms interfere with and reduce the quality of his life, and symptoms “are not better explained by another mental disorder” (APA, 2022, p. 69). Due to the client’s presenting issues, signs, and symptoms, the counselor believes that at this time, the most accurate and fitting diagnosis is F90.2: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, combined presentation, moderate severity (APA, 2022).

Conceptualization

Cognitive Behavioral Theory

The counselor will begin the conceptualization with a CBT approach to the client’s presenting issues and integrate RCT and PDT in subsequent sections. CBT was developed by Aaron T. Beck and is predicated on the belief that dysfunctional thinking leads to all psychological disturbances (Beck, 2021). Dysfunctional thinking and maladaptive core beliefs negatively influence a client’s mood/emotions and behaviors (Beck, 2021). Beck (2021) states, “When people learn to evaluate their thinking in a more realistic and adaptive way, they experience a decrease in negative emotion and maladaptive behavior” (p. 4).

When viewed through the CBT lens, it will be necessary for the counselor to first assist the client in discovering his underlying core beliefs and associated automatic thoughts (Beck, 2021). Once his negative core beliefs are identified, the counselor will assist Michael in understanding how his thoughts influence his emotions and subsequently affect his behaviors and actions, particularly his angry outbursts toward his wife and his reluctance to attend college (Sokol & Fox, 2019). Additionally, it will be demonstrated to the client that his maladaptive behaviors further affect his thoughts, emotions, and circumstances, thus creating more maladaptive behaviors that only perpetuate the cycle (Beck, 2021).

The client’s anger and emotional reactivity, in part, are a result of his unmanaged ADHD symptoms (Sokol & Fox, 2019). In addressing the client’s anger, the counselor is not attempting to eliminate the emotion but rather to assist the client in recognizing the erroneous thinking that precedes his angry outbursts (Sokol & Fox, 2019). Next, the counselor and client will identify his “strengths, personal qualities, skills, and resources” to bolster his self-esteem (Beck, 2021, p. 7). Additionally, psycho-education, cognitive restructuring, and medication are essential in increasing the client’s inhibitory control, thus decreasing his emotional reactivity (Young et al., 2020). Once the client has identified his strengths and can think more positively, his emotions and behaviors will become more adaptive, and his circumstances will improve (Young et al., 2020).

Relational Cultural Theory

When considering the client's culture and upbringing, the counselor will integrate RCT into this conceptualization. Jean Baker Miller founded RCT in the late 1970s with the help of Irene Stiver, Judith Jordan, and Janet Surrey (Jordan, 2018). RCT was developed in response to the male-dominated field of psychodynamic theories that misrepresented women’s lived experiences (Schwartz, 2021). RCT’s central tenets revolve around the importance of growth-fostering relationships, mutual empathy, and mutual empowerment (Miller, 2008). Further, Jordan (2018) states that “chronic disconnection is the source of enormous suffering and that healing people’s experience of isolation is one of the central tasks of psychotherapy” (p. 19).

RCT posits that early relationships are foundational in an individual’s development (Jordan, 2018). Michael expressed having a poor relationship with his father and difficulty recognizing and expressing his emotions due to his father’s rigid and traditional view of masculinity that he instilled in Michael as a boy. It is generally recognized among psychologists that gender is more than a biological construct, and societal/cultural norms have a significant influence on gender and mental health (Bryde et al., 2023). Traditional masculinity values stoicism, aggression, individualism, and restricting one’s emotions (Bryde et al., 2023). Stoicism, aggression, and individualism are the antithesis of RCT therapists' values for growth-fostering relationships and only increase isolation and disconnection (Jordan, 2017). In the spirit of RCT, the counselor will work with Michael to deepen his relationships, decrease his feelings of isolation, and become emotionally fluent. The counselor will also explore the client’s views on masculinity and his strategies of disconnection that protect him from being hurt by others and forming vulnerable connections (Jordan, 2018).

In assisting the client in forming growth-fostering relationships, the counselor will practice mutual empathy during sessions. Mutual empathy is the counselor’s “openness to being affected by and affecting another person” (Jordan, 2018, p. 135). The counselor will be responsive to the client and reveal the impact that he has on the counselor. A sense of community is created when two people share vulnerably and know that each one matters to the other (Schwartz, 2021). In this way, the counselor will model a growth-fostering relationship.

To deepen the exploration of Michael’s relationship with his father and his inability to form vulnerable friendships with other men, the counselor will explore what RCT terms the “central relational paradox” with the client (Jordan, 2018). When people feel disconnected and isolated, they may yearn for more relational connection, but they fear engaging with others in a vulnerable capacity and thus remain disconnected (Jordan, 2018). Further, Michael stated that he conformed his personality to fit his father's expectations as a child and, in the process, sacrificed authenticity and mutuality, which served to deepen the disconnection between him and his father that remains today (Jordan, 2018).

Psychosocial Developmental Theory

Erik Erikson developed his eight stages of psychosocial development as a model that encompassed the entirety of the lifespan and incorporated relationships as an essential driver in development (Knight, 2017). In contrast, many of his contemporaries only focused on childhood and the individual (Knight, 2017). Each of Erikson’s eight stages corresponds to a unique developmental period in an individual’s life and is characterized by a dichotomy (Maree, 2021). Each dichotomy is considered a crisis that an individual must overcome in order to meet the challenge of each stage (Erikson, 1963). For example, the first stage is called trust vs. mistrust, and to successfully meet the challenge of this stage, an infant must not only learn to trust its caregivers but also discern when to mistrust. The goal is not to favor one over the other but to integrate a capacity for both (Knight, 2017). Meeting the challenge at each stage is essential for successfully navigating the following stages. Not meeting the challenge of the preceding stages impairs the individual’s growth through subsequent stages (Knight, 2017). “In a related sense, all previous stages begin to form the personality structure, and all previous stages have echoes in the current stage that influence how future stages are negotiated” (Knight, 2017, p. 1049).

Michael is currently in the sixth stage of development: intimacy vs. isolation. Erikson described intimacy as the capacity to sacrifice, compromise, and commit to another individual while losing yourself “so as to find one another in the meeting of bodies and minds” (Erikson, 1982, p. 67). Michael expressed having difficulties in his marriage that include regular fighting, lack of intimacy, and a lack of mutual support. The counselor will not only delve into the traits of stage six with the client but will first want to determine whether he met the challenge of stage five, called identity vs. confusion (Knight, 2017).

To engage in healthy, intimate partnerships, one must meet the challenges of stage five, including becoming independent and having a fully formed sense of self (Erikson, 1963). Michael stated that during his adolescent years, he was in an unhealthy romantic relationship where he sought his worth and identity through his partner and never found his true identity. The counselor will assist the client with identifying traits and characteristics that represent his genuine identity. Having a better understanding of his identity, Michael will rise to the challenge of stage six and be better able to fuse his true self with his partner and form a healthy, intimate relationship (Erikson, 1963). Additionally, the counselor will address the client’s isolation and disconnection that he feels toward his father and assist him with forming an intimate bond with him. If the client can successfully meet the challenges of stages five and six, he will be responsive and ready for stage seven when it arrives (Knight, 2017). Stage seven, called generativity vs. stagnation, is marked by the capacity of an individual to nurture things that will outlive them and give back to their communities (Erikson, 1963). It remains to be seen how Michael will care for others, how he will benefit his family and community during stage seven, or whether or not he and his partner will have children to nurture; however, having met the challenges of previous developmental stages, he will be well prepared (Knight, 2017).

Treatment Plan

| Counseling Treatment Plan | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name: Michael | Date: March 10, 2024 | |

| Problem: The client experiences emotional reactivity due to untreated ADHD symptoms, and his angry outbursts are negatively affecting his marriage. Additionally, the client has low self-esteem, negatively impacting his relationships and preventing him from attending college. | ||

| Goals: 1. The client will learn necessary skills to improve his anger management/emotional reactivity while enhancing his relationship with his wife. 2. The client will develop positive self-talk and core beliefs while increasing his self-esteem. | ||

| Goal One Objectives | Goal One Interventions | |

| 1. The client will journal his automatic thoughts that arise just before an event or situation that causes him to react in anger. | 1.a. In a conjoint session, have the client share his automatic thoughts and the associated emotions that he journaled about. Next, assist the client with determining how his thoughts and emotions affect his angry behaviors. | 1.b. The counselor will educate the client on the subtle difference between reacting and responding. The counselor and client will role-play examples of healthy responses vs. angry reactions. |

| 2. The client will list three unrealistic demands that he places on his wife and replace them with reasonable requests | 2.a. The counselor and client will explore what his unmet demands are and the roots of them. Have the client identify and list the distortions in his thinking about his unmet needs. | 2.b. Have the client imagine a role reversal with his wife where he experiences the demands of his unmet needs first hand. Have the client explore and list his emotions during the role reversal |

| Goal Two Objectives | Goal Two Interventions | |

| 1. The client will list five instances between sessions where he practices positive self-talk. | 1.a. In a conjoint session, have the client describe and list the emotions that he experiences when he practices positive self-talk. To increase the client’s self-esteem the counselor will practice mutual empathy and allow the client to see how he impacts the counselor thus validating his positive self-talk. | 1.b. In session, have the client explore the roots of his negative core beliefs and negative self-talk and assist him with positively reframing them |

| 2. The client will identify and list his fears and anxieties about attending college. | 2.a. The counselor and client will explore his exaggerated perception of the probability of failure, consequences of attending college, and his underestimation of how to cope with his fears. Have the client list five positive internal resources that he possesses that reframe his thinking. | 2.b. In a conjoint session, assist the client with modifying his inaccurate and anxious thoughts/fears into a proactive list of steps that will empower him and increase his confidence in attending college |

| Strengths & Resources: Michael is genuinely motivated to change and is creative, reflective/self-aware, and personable. | ||

| Current Diagnosis: F90.2: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, combined presentation, moderate severity. | ||

Rationale for Treatment Plan

In the treatment plan, the counselor used primarily CBT interventions as they are particularly effective for clients with ADHD (Sokol & Fox, 2019), whereas RCT and PDT focus more on relationships than interventions (Jordan, 2018; Knight, 2017). In a recent meta-analysis, López-Pinar and colleagues reviewed twelve studies that included 1,073 participants on the efficacy of CBT for treating ADHD (2018). The authors of the study state that, combined with medication, CBT interventions have a lasting effect on neuropsychiatric deficits and dysfunctional thinking in ADHD clients that lasted up to twelve months after treatment (López-Pinar et al., 2018).

Although RCT and PDT do not rely heavily on interventions (Jordan, 2018; Knight, 2017), the counselor infused elements of both theories into the treatment plan to bolster the efficacy of the interventions. It will be essential to explore relational images and strategies of disconnection while practicing mutual empathy and empowering the client (Jordan, 2018). Further, the counselor will discuss the client’s previous and current psychosocial developmental stages, whether he met the challenge of the previous stage, and if he is on course to meet the challenge of his current stage (Knight, 2017).

Model Integration

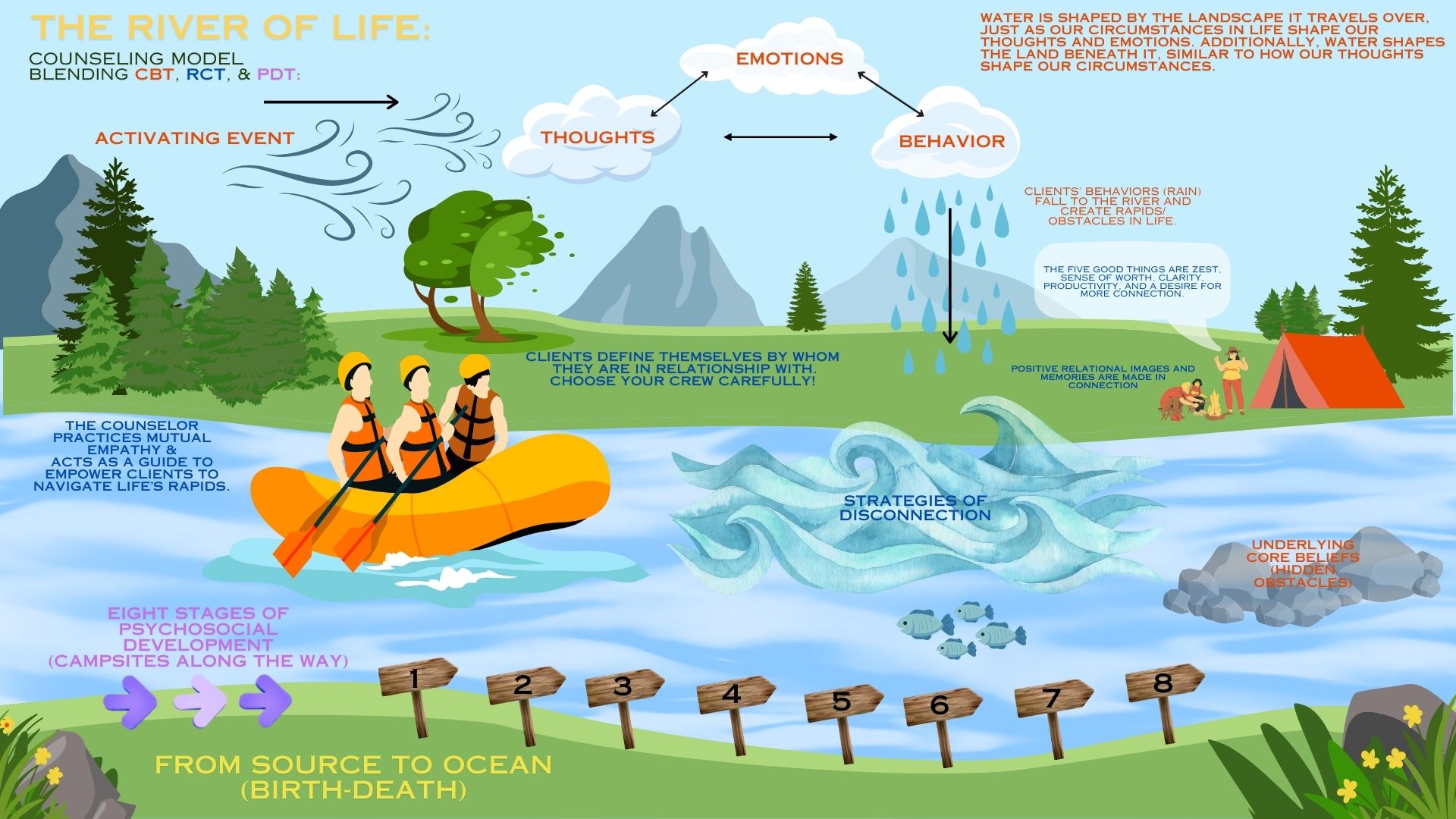

The River of Life (ROL) is the counselor’s model for conceptualizing individual clients’ unique challenges, presenting issues, and desires/goals. The model blends CBT, RCT, and PDT. The counselor will describe the model in detail and demonstrate how it can be used in four domains of individual well-being.

The River of Life

Water is shaped by the landscape it travels over (e.g., a wave in a river and the underlying rock beneath the surface), just as clients’ thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are shaped by their circumstances (Beck, 2021). At the same time, water shapes the land beneath it (e.g., deep canyons or meandering river valleys), similar to how clients’ thoughts can positively shape their behaviors and change their circumstances. The relationship between water and the landscape is reciprocal in nature, just as clients’ thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are (Beck, 2021). Each one affects the other.

While navigating the river of life, it is essential that clients fill their boats with growth-fostering relationships and a guide (counselor) who knows the terrain when the rapids of life begin to crash upon the bow. A skilled guide/counselor will empower clients, practice mutual empathy, increase clients’ relational resilience “in the face of adverse conditions,” and keep them in the boat when they attempt to jump ship as a disconnection strategy (Jordan, 2018, p. 138). As the days become weeks, months, and years on the journey down the river of life and clients grow older, the guide will counsel them through each of the stages of psychosocial development and ensure that they meet the challenge of each stage (Knight, 2017).

Relational Domain

When considering the relational domain of the human experience, the counselor will use the ROL model to demonstrate an effective counseling strategy for clients. Jordan (2018) writes, “Early and ongoing relationships shape much of a person’s life” (p. 16), and the goal of an adequately individuated person is to move from “disconnection to connection” (p. 8). Although clients do not choose their early caregivers, they must choose carefully whom they travel the river of life with. Both RCT and PDT posit that healthy relationships are integral to a well-lived and meaningful life (Knight, 2017; Miller, 2008), and many of clients’ relational challenges stem from isolation and negative core beliefs about themselves (Beck, 2021; Schwartz, 2021). When clients seek counseling due to isolation or trouble with their relationships, the counselor will first explore their underlying core beliefs about self-worth and seek to reframe their negative beliefs into adaptive ones (Dwyer et al., 2011). For example, clients in their young adult years face Erikson’s sixth stage, intimacy vs. isolation. They must meet the challenge of this stage to find meaningful growth-fostering relationships and romantic partners (Erikson, 1982). The counselor working within the ROL model will work with the client to resolve unmet challenges of previous psychosocial stages while introducing RCT’s “five good things” for building growth-fostering relationships (Jordan, 2017). Clients will be encouraged to create zest or energy and enthusiasm in their lives, build their self-worth, find clarity around what they desire in relationships and partners, become productive in their self-care and pursuit of relationships, and seek more connection throughout life (Schwartz, 2021).

Religious and Spiritual Domain

Religion and spirituality have many mental health benefits, including subjective well-being, resiliency, optimism, improving symptoms of anxiety and depression, and acting as a protective factor against suicidality (Yoon et al., 2021). In his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, Victor Frankl (1984) wrote that his religious and spiritual beliefs gave him strength and resilience to face the horrors of Nazi concentration camps and even found meaning, hope, and purpose when imprisoned (Yoon et al., 2021). From a wellness-based and holistic approach, it is important for counselors to integrate religion and spirituality with clients’ search for meaning and improve their mental health (Yoon et al., 2021).

In the ROL model, life is viewed as a journey downriver. From source to ocean, clients live their lives in search of meaning, purpose, and loving relationships. The river shapes them with every paddle stroke; they find strength and persevere through life’s most challenging rapids with those paddling alongside them. The ROL model is infused with flexible analogies for clients to frame their religious or spiritual beliefs, whatever they may be.

To illustrate, a young adult comes to counseling seeking purpose and meaning in life but has been harmed by organized religion as a child and is resistant to exploring his spiritual beliefs. Since the ROL model is not associated with any one religion or spiritual practice, the counselor and client can be creative and use the model to explore his spirituality without negative associations from his past. The counselor will infuse elements of RCT, including working with the client on his early relational images about religion, those “inner pictures of what has happened to [him] in relationships, formed in important early relationships” (Jordan, 2018, p. 138). Additionally, the counselor will help the client identify triggering events and his associated automatic thoughts about his disdain for religion and assist with reframing them (Dwyer et al., 2011). The client’s psychosocial developmental stage and how it relates to his spiritual beliefs will also be explored.

Education and Career Domain

To illustrate the effective use of the ROL model in education/career, the counselor will introduce a client scenario and describe the treatment process. A 45-year-old female client seeks counseling due to her apprehension about attending college as an older student to obtain a degree in social work. She is a mother of two adult children who have recently moved from the household. The client is in despair about whether she is leading a meaningful life now that her identity as a mother is shifting. She wants to contribute to a cause greater than herself as she ages and find fulfillment and purpose.

In Erikson’s stages of development, the client is in the generativity vs. stagnation stage (Erikson, 1982). During the seventh stage of life, it is developmentally appropriate for her to seek a cause greater than herself, give back to her community, and stave off feelings of stagnation, loneliness, and depression (Christiansen & Palkovitz, 1998). The counselor will draw upon an analogy from the ROL model to assist her in normalizing her fears about attending college. It will be described to the client that while traveling the river of life, it is natural to feel anticipatory anxiety before entering dangerous rapids. However, having met the challenge of navigating the rapids (stage seven) successfully, she will be well suited to meet the challenge of the next rapids/stage, called integrity vs. despair (Erikson, 1963). Further, the counselor will discuss the quality of her growth-fostering relationships with the client, draw upon her strengths, and reframe her negative core beliefs about her age and ability to meet life's challenges into adaptive thinking and behaviors (Beck, 2021).

Physical Domain

In the physical domain, the counselor will focus on nutrition, exercise, and sleep and their impacts on an individual’s mental health and relationships. Poor sleep and stress impact people’s ability to make healthy choices regarding diet and exercise and decrease immune response (Nathan et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2018). An individual who slept poorly the night before is more likely to eat unhealthfully, avoid exercising, and is prone to becoming ill; as a result, their mental health and relationships suffer (Nathan et al., 2020).

For example, an out-of-shape, lethargic client seeks counseling because he is stressed and fatigued, and as a result, he is depressed, and his wife wants a divorce. The counselor working within the ROL model will liken diet, exercise, and sleep to tools (maps, oars, etc.) used to navigate the river of life successfully. Further expanding on the river analogy, the client is described as stuck in a circulating eddy, separate from the river’s flow, stuck in place by his limiting beliefs and low self-esteem. With the counselor's help, the client will uncover the core beliefs that affect his self-worth and work to reframe them to encourage healthy lifestyle choices/behaviors (Beck, 2021). Additionally, the counselor will encourage the client to find zest for life and work on the “five good things” to improve his relationship with his wife (Schwartz, 2021). Having improved his lifestyle habits, the client will no longer watch life pass him by, stuck in an eddy; he will re-enter the flow of life, and consequently, his marriage will improve.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed. Text rev.). Link

Beck, J. S. (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. The Guilford Press.

“Men are not raised to share feelings” Exploring male patients’ discourses on participating in group cognitive-behavioral therapy. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 31(1), 3–24.Link

Christiansen, S. L., & Palkovitz, R. (1998). Exploring Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development: Generativity and its relationship to paternal identity, intimacy, and involvement in childcare. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 7(1), 133–156. Link

Dwyer, L. A., Hornsey, M. J., Smith, L. G. E., Oei, T. P. S., & Dingle, G. A. (2011). Participant autonomy in cognitive behavioral group therapy: An integration of self-determination and cognitive behavioral theories. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(1), 24–46. Link

Erikson, E. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Jordan, J.V. (2017). Relational–cultural theory: The power of connection to transform our lives. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56: pp. 228–243. Link

Jordan, J. V. (2018). Relational-cultural therapy (Second edition.). American Psychological Association.

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E., Howes, M. J., Jin, R., Secnik, K., Spencer, T., Ustun, T. B., & Walters, E. E. (2005). The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(2), 245–256. Link

Knight, Z. G. (2017). A proposed model of psychodynamic psychotherapy linked to Erik Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(5), 1047–1058. Link

López-Pinar, C., Martínez-Sanchís, S., Carbonell-Vayá, E., Fenollar-Cortés, J., & Sánchez-Meca, J. (2018). Long-term efficacy of psychosocial treatments for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 638–638. Link

Maree, J. G. (2021). The psychosocial development theory of Erik Erikson: Critical overview. Early Child Development and Care, 191(7–8), 1107–1121. Link

Miller, J. (2008). Connections, disconnections, and violations. Feminism and Psychology, 18(3), 368-380. Link

Morrison, J. R. (2014). Diagnosis made easier, second edition: Principles and techniques for mental health clinicians. Guilford Publications

Nathan, N., Murawski, B., Hope, K., Young, S., Sutherland, R., Hodder, R., Booth, D., Toomey, E., Yoong, S. L., Reilly, K., Tzelepis, F., Taylor, N., & Wolfenden, L. (2020). The efficacy of workplace interventions on improving the dietary, physical activity and sleep behaviours of School and childcare staff: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4998-. Link

Schwartz, H. (2021, January 25). Exploring relational cultural theory: In conversation with Dr. Judith V Jordan ep 1 early history [Video]. YouTube. Link

Smith, T. J., Wilson, M., Karl, J. P., Orr, J., Smith, C., Cooper, A., Heaton, K., Young, A. J., & Montain, S. J. (2018). Impact of sleep restriction on local immune response and skin barrier restoration with and without “multinutrient” nutrition intervention. Journal of Applied Physiology (1985), 124(1), 190–200. Link

Sokol, L., & Fox, M. G. (2019). The Comprehensive Clinician's Guide to Cognitive Behavioral therapy. PESI.

Yoon, E., Cabirou, L., Hoepf, A., & Knoll, M. (2021). Interrelations of religiousness/spirituality, meaning in life, and mental health. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(2), 219–234. Link

Young, Z., Moghaddam, N., & Tickle, A. (2020). The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adults With ADHD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(6), 875–888. Link