Coming out of the Dark: How an Accurate Diagnosis Helped Me Reclaim My Life

Shauna Graves | May 1, 2021 | 12 min read

Forward

The article provides an in depth and personal exploration of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Shauna's insight and vulnerability into this debilitating condition is inspiring. We are honored to share her story.

“My dark days made me strong. Or maybe I was already strong, and they made me prove it.” - Emery Lord

For the past 20 years, I've struggled with mental illness. I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder as a freshman in college and treated with psychiatric medications. During my late teens and 20's, I suffered from intense bouts of anxiety and panic attacks that often hit without warning or a known trigger. My mood changes became more cyclical about ten years ago, so I sought the expertise of a psychiatrist who diagnosed me with bipolar II disorder. While I initially struggled to accept the stigma related to having this disorder, I eventually accepted it as a part of my identity. The bipolar II diagnosis followed me from one medical professional to another over the years—down the line of psychiatrists, therapists, specialty clinicians, and primary care providers. I was treated with various cocktails of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics. I was stable, for the most part, for many years. Until I wasn't.

My “anxiety cycles,” as my loved ones and I called them, began increasing in frequency and severity about three years ago. Rather than occurring 2-3 times per year, they were hitting nearly every four weeks. They severely disrupted my daily routine, causing me to miss multiple days of work each month, robbing me of my confidence and joy, interfering with personal and professional relationships. I started to track the cycles on a calendar and noticed a pattern developing. My partner, Jeff, noticed a pattern too (actually, long before I did). He believed that my anxiety cycles were hormone related. I initially discounted his idea, convinced that my bipolar meds needed tweaking. At that point, I was seeing my psychiatrist almost weekly, who was constantly adjusting my medications. He ordered lab tests, a brain MRI, and an EEG to rule out organic causes for these debilitation cycles. The tests came back normal, but something was clearly wrong. The cycles continued.

A week in the life

I feel a bit “off” for a few days: tired, irritable, stressed, withdrawn. I go about my daily activities, pushing through the discomfort of feeling out-of-sorts. Then a few nights later, I awake from my deep sleep with a sharp, stabbing jolt of panic in my chest. My mind is spinning, heart pounding, hands trembling. I get out of bed and pace around the house with anxious energy. I tell myself to sit down and take some deep breaths, but I can't expand my lungs and my breath gets caught in my throat. I pace the room and hyperventilate through pursed lips. I check the clock—3:30 am—three hours until my alarm is set to go off. I take an antianxiety pill and lay back down, in-and-out of restless sleep until my alarm wakes me in a panic. My head pounds, my stomach churns, my body aches. “You can do this, one-step at a time,” I tell myself. Jeff reminds me of the same and gives me a comforting hug. I painstakingly get myself and my son ready for the day, drop him off at school, and head to work. I stare at my computer with tunnel vision, trying to ignore the hurricane surging inside me—before I succumb. Turns out I can't do it. I leave work in tears, feeling ashamed, exhausted, and completely defeated.

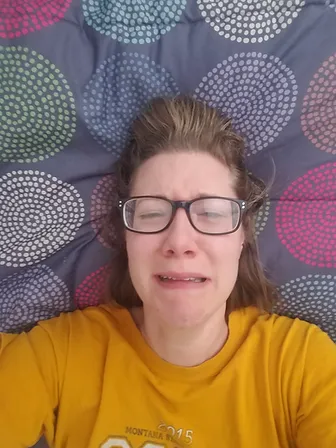

The next 3-4 days are spent in lonely isolation, a prisoner of my own brain and body. I have no appetite, energy, motivation, or desire to do anything. I am in a constant state of flight-or-fight, panic surging through every cell in my body like an electric current, anxious thoughts ping-ponging around in my brain. I spontaneously melt into a puddle of tears, consumed by feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness. The only relief from the intense anxiety and dark depression, although temporary, is clonazepam (Klonopin) and sleeping. I drift off to sleep, but the meds wear off quickly and panic returns. I jolt upright in bed and my 9-year old son comes in to check on me, gentling reminding me, “It's ok mama, just breathe.” One painstaking hour bleeds into the next, one endless day into another. I try explaining to others how miserable I am, but I can't find the right words to express the severity of what I've experiencing. So, I retreat deeper into my own darkness.

Days later, the storm lightens a bit, and finally the sun emerges from the clouds. The past week is a blur, many details which I cannot remember nor want to relive in my mind's eye. I am indebted to my loved ones, who have been holding the pieces of my life together while I am incapable of doing so. I am relieved to feel like myself again yet exhausted from fighting this battle against an unknown enemy. I put on a brave smile and return to the world, all the while dreading the next cycle that is inevitably on the horizon.

Symptom Tracking

My psychiatrist and I both acknowledged that my condition wasn't improving. I was doing the “right” things for my physical and mental health: eating well, taking vitamins and supplements, limiting alcohol and caffeine intake, exercising, going outside for fresh air and sunlight, getting adequate sleep, practicing mindfulness and deep breathing. Yet my cyclical condition continued to get worse, not better. Because I had a hormonal-implanted IUD, I was not having regular periods. Jeff theory that my cycles could be hormone-related, was starting to sound more probable as time went on. As my primary care provider removed my IUD, I explained that the process allowed me to track my menstrual periods alongside my anxiety cycles. During the visit I also asked if she could order labs to check my hormone levels. When my PCP replied with a confused expression, “Why? Your hormone levels are always fluctuating.” I felt that she was dismissing my intuition that my menstrual cycles were driving my mood symptoms. However, after a few months post-IUD, the pattern became truly clear. Two weeks before my period I would start to feel “off,” then I would suffer through a week of debilitating anxiety, and eventually the storm would subside once my period started.

Not Alone

I began reading online about a condition called PMDD, one which I briefly heard about in nursing school. I landed upon a website called The International Association of Premenstrual Disorders (iapmd.org) and clicked on a link to a video. I listened and watched as women shared their raw, heartbreaking experiences of living with premenstrual disorders. Their stories were my story. Tears streamed down my face as I clung to every word they said. For years, I was convinced I was the only person in the world suffering from these debilitation anxiety cycles, that I was crazy and incurable. But in that moment, I realized I wasn't alone.

Mayo Clinic

Desperate for answers, and strongly suspecting I had PMDD, I asked my psychiatrist for an outside referral. In February 2020, Jeff and I went to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN where I underwent a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation. My diligent symptom tracking, along with Jeff's observations and insight as my caregiver during so many vicious cycles, provided valuable information for the Mayo experts. Not only did they diagnose me with PMDD, but they determined I had been misdiagnosed, and therefore mistreated, with bipolar II disorder. Hearing their words filled me with hope and validation. Finally, an answer.

PMDD

PMDD, which stands for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, is defined as a cyclical hormone-based mood disorder with symptoms arising during the premenstrual, or luteal phase, of the menstrual cycle and subsiding within a few days of menstruation. Although PMDD is classified as a mental illness in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), it is also considered an endocrine disorder. Surprisingly, PMDD is not a hormone imbalance, rather it is a “severe negative reaction to the natural rise and fall of estrogen and progesterone,” causing anxiety, depression, irritability, anger, lack of energy, feelings of hopeless, and even suicidality (IAPMD). Unlike other medical conditions, there is no clinical lab or diagnostic test for identifying PMDD. Rather, diagnosis requires detailed symptom tracking on behalf of the patient, and ruling out other medical conditions, like thyroid disease.

As I learned about premenstrual disorders, I was appalled to discover that an estimated 5- 8% women of child-bearing age worldwide suffer from this condition. Shockingly, it takes an average of 12 years to get a correct PMDD diagnosis (IAPMD). The disruptive toll this condition takes on one's quality of life is extreme. According to MGH Center for Women's Mental Health (2020), “women with untreated PMDD were likely to experience a loss of three quality-adjusted life years during their lifetime as a result of premenstrual symptoms.” I can certainly relate to that statistic, considering that I lost nearly two quality weeks of my life each month in recent years.

Last Resort

After returning from Mayo with a fresh diagnosis, I established with a local ob/gyn who was familiar with PMDD (and coincidentally, was my obstetrician when I was pregnant with my son). She started me on an SSRI antidepressant (Prozac) in conjunction with hormone replacement therapy, which is considered 1st/2nd line treatment for PMDD. Although my symptoms improved slightly over the next few months, the cycles continued. My next treatment option was a trial of chemical menopause, which essentially shut my ovaries off and eliminated the monthly fluctuations in hormones. I responded relatively well to this treatment, but when a debilitating PMDD cycle hit me in October 2020, I decided one more cycle was one too many. After hours of meticulous research, weighing the pros and cons, and approval from my trusted medical providers (including a new psychiatrist with experience treating PMDD), I made the drastic decision to undergo an elective surgery to have both ovaries removed. Known as an oophorectomy, this is considered the last line treatment for PMDD. The decision to have my ovaries removed was not taken lightly: it would cause infertility and thrust me into instant, irreversible menopause. Yet, the possibility of living free from PMDD far outweighed the downsides of surgery, so I had my ovaries removed in November 2020. Now, five months later, I am elated to report that the dark cloud of PMDD has lifted—and I have reclaimed my life.

Hope for the Future

Why have so many, like me, never heard of PMDD? Why is it so often overlooked by medical experts, grossly underdiagnosed, and improperly treated? It's time for PMDD to become a conversation in the mainstream medical community, and a conversation in general. I was recently selected to be a member of a patient insight panel with IAPMD, the same organization that was a lifeline to me in my darkest days. I, along with nearly 30 other women from different parts of the world, am sharing my opinions and experience living with PMDD to guide future research and bring much-needed light to this condition that impacts so many. Moving forward, I'm committed to focusing not on what I've lost, but what I've gained. Rather than harboring bitterness over the years of suffering, the missed opportunities of many healthcare providers to re-examine my bipolar II diagnosis, the thousands of dollars spent in failed treatment, the dramatic impact of my debilitating condition on my loved ones—I chose to focus on living, and living well.

Shauna Graves RN is a registered nurse who works with vulnerable populations at a federally qualified health center. As a colleague I have learned a considerable amount from her. She has really opened my eyes to the importance of identifying and treating PMDD. We are lucky to have her contribute her unique perspective.

References

MGH Center for Women's Mental Health. (2020).Link

What is PMDD? (2019). International Association for Premenstrual Disorders. Link